Two years ago, when the centenary of pneumonic flu, more commonly known as the Spanish flu, was celebrated, Portuguese historians again wondered why one of the most deadly episodes in recent history had almost eclipsed the collective memory.

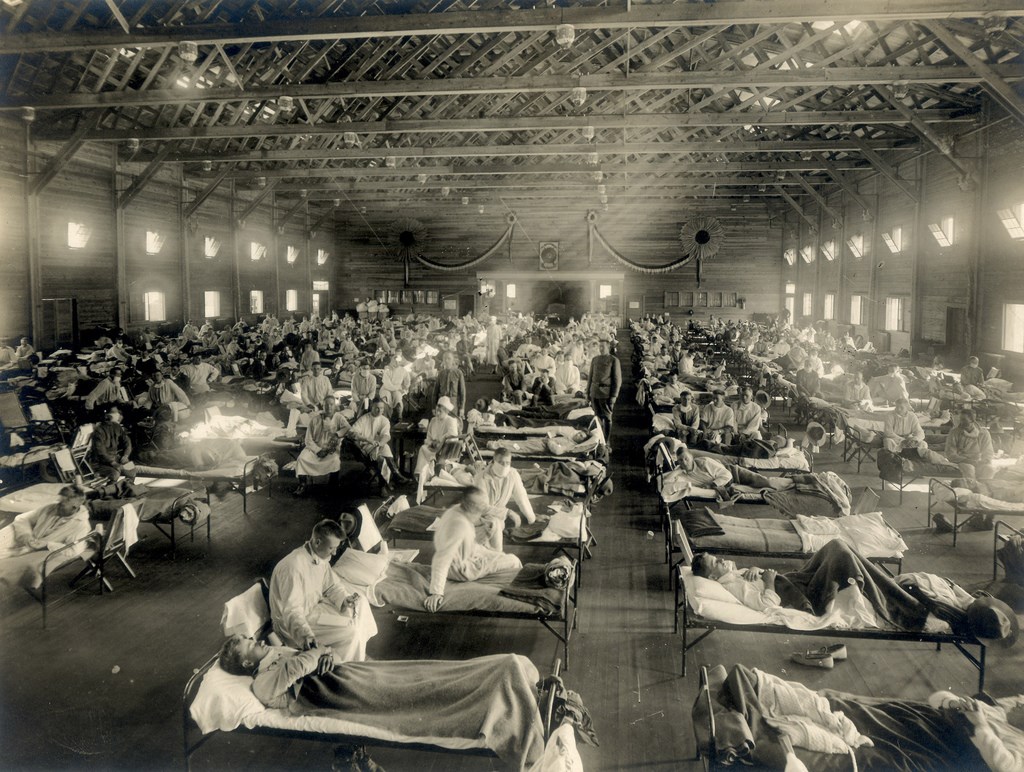

The books The Forgotten Pandemic: Comparative Views on Pneumonia (1918-1919), published in 2009, and Pneumonic Flu Centenary: Pandemic in Retrospective, published at the time of the centenary in 2019, do not differ much in tone: even in Portugal, where pneumonia is estimated to have caused 136,000 deaths in a country with six million inhabitants, one of the highest mortalities in Europe, the devastation caused has not of the epidemic an event whose memory would last. “Monuments to the victims of the epidemic are very rare”, writes historian José Manuel Sobral, from the Institute of Social Sciences, in the centennial work, while those dedicated to the dead of the city proliferate. World War I (1914-1918), in which the last fighting coincided with the peak of the pandemic – 1341 Portuguese soldiers died on the European front.

In terms of mortality, this neglected disease for which the world is now looking scared of the covid-19 was the greatest demographic disaster of the 20th century and probably the most serious pandemic to hit the world since the Black Death, or bubonic plague. , in the 14th century. In Portugal, 1918 was the only year in which there was more deaths than births – since the flu mainly hit younger people – looking at the records andbetween 1886 and 1993.

“The fact that there are pandemic episodes always makes us think in the worst pandemic of all. There was also talk of pneumonic flu when there was an outbreak of influenza A in 2009, which was also felt in Portugal ”, recalls historian José Manuel Sobral in an interview with PÚBLICO. Before the current crisis, it was the last time that the World Health Organization issued a pandemic change, but 11 years ago there were only 124 deaths in Portugal out of 200,000 cases.

What can the 1918 flu teach us, after all? current pandemic? – is a recurring question in the press in recent days.

“In the spring of 1919, when the virus was going out, a third of the world’s population had been infected and at least 50 million people had died. Over 40 million more have died in the death camps in Flanders and Northern France [I Guerra] and 10 million more of those who have died of AIDS in the last 40 years since the syndrome was recognized in the 1980s, ”writes medical historian Mark Honigsbaum last week at New York Review of Books, also inquiring about historical amnesia. On the contrary, in its few months of life, SARS-CoV-2, the official name of the new coronavirus, has already provoked the crash of the exchanges, left the aviation industry on the ground and provoked successive declarations of state of emergency with the movements of the world population severely restricted, he argues.

As in 1918, SARS-CoV-2 is an unknown virus against which there is no vaccine, notes historian José Manuel Sobral, stressing, however, that there seem to be very different traits between the two. “Pneumonic flu infected and killed much faster than covid-19. But in the face of previous episodes of coronavirus, such as SARS in 2002 or MERS in 2012, the new coronavirus is showing a great capacity for spreading and killing a large number of people. It is generating great concern and emergency measures enacted everywhere ”, he says. Outbreaks by the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV viruses fell short of the 1,000 killed worldwide, while SARS-CoV-2 has already killed 24,000 people.

As for the development of the disease, pneumonia and covid-19 show similar characteristics, because both affect the respiratory tract, degenerate into pneumonia and can be deadly, recalls the British author Mark Honigsbaum in the same article, author of the book The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris (2019). The two viruses, however, are very different pathogens: “Although both spread through the respiratory tract through droplets from coughing or sneezing, the coronaviruses do not transmit as efficiently as aerosols as we see in the flu. In fact, it is thought that SARS-CoV-2 does not present a risk at distances greater than two meters. The main form of transmission seems to be prolonged social contact, as it happens at family gatherings. ”

Very, very lethal

The first news about the pneumonic flu in Madrid is dated May 20, 1918. A primacy that led to the disease being mistakenly baptized as Spanish flu, as it must have appeared in March among soldiers at Camp Funston, a camp. US Army training in Kansas – the most commonly agreed hypothesis about the origin of pneumonia. In Portugal, eight days after the news in Spain, Ricardo Jorge, the general director of Health at the time, informed the Superior Hygiene Council that the disease was spreading rapidly throughout the neighboring country, according to a note published in the newspapers on 28 March. May 1918.

Ricardo Jorge in a laboratory in Porto in 1899

Aurélio Paz dos Reis / CPF

Pneumonics developed in Portugal through three waves, as in the rest of the world, explains José Manuel Sobral. “The flu begins among harvesters who came from the border area with Spanish Extremadura, but the first phase was not particularly ferocious.” He arrived in Portugal at the end of May with agricultural workers infected from outbreaks in Badajoz and Olivença, the first cases being diagnosed in Vila Viçosa. From there, it expanded to other Alentejo villages and then to the rest of the country. It peaked at the end of June, then declined suddenly.

“But at the end of August the second outbreak begins, which will reach its peak in October-November. This is very, very, very lethal ”, Sobral continues. The second wave started to manifest itself in the Porto area, in Gaia, radiating immediately to Minho and Douro, with cases also appearing in the center of the country. From September, the epidemic moved south and in early October it reached the Algarve. As for the third wave, which would arrive in April and May 1919, it already had much less deadly characteristics and there is little data on it.

“The speed at which the disease spread did not leave much time to consider defense measures,” writes the historian, adding that mortality and virulence were higher than any other serious epidemics recorded previously, such as yellow fever (1856) and cholera (1857), which occurred in Lisbon, and also bears no resemblance to previous outbreaks of influenza, such as that of 1889-1890.

No special measures are taken during the summer of 1918, because this is a virus – as Ricardo Jorge and a large part of the international medical community thought, which was confirmed in the 1930s through the electron microscope -, only a natural immunization or a vaccine could prevent the disease. “On the other hand, Portugal, like much of the world, was a country where the presence of epidemics was a constant. So one that was not noted for a very high mortality was a problem like the others. ” In 1918, epidemic outbreaks of smallpox, typhoid, exanthematic typhus and dysentery were seen in Portugal. Tuberculosis killed thousands of young adults and in that year alone, its mortality was overtaken by pneumonic flu.

–

NIAID Credit

The hecatomb, however, was being announced. On 29 September, the Director-General issued the first official instructions with detailed combat on six points. The first organized an information system, asking all doctors to report cases to health deputies. The second noted that it was necessary to avoid population movements.

On October 6, 1918, by decree No. 4872, Ricardo Jorge, the most important Portuguese health authority, was appointed Commissioner-General of the Government to direct the fight against the epidemic. “What will transform everything into something different is the breadth and speed of the epidemic, in a terrific context, which was the war, the supply crisis, in a country that already had enormous needs, where the medical-sanitary apparatus itself, when existed, it was frankly in need. ”

In 1920 there were 2580 doctors in Portugal, which gave one doctor per 2338 inhabitants, while currently there is one per 189 inhabitants (figures for 2018 for the Continent). But the average of the beginning of the century is misleading, because in a territory where almost half of the population lived, there was neither medical assistance nor pharmacies. It is also necessary to take into account that 640 of these professionals were incorporated in the three fronts of war.

A couple on a London street during pneumonic flu, where deaths reached 4,500 a week in October 1918

“The lack of everything is an eloquent testimony to the President of the Republic’s train journey to the North,” writes Sobral in the book dedicated to the centenary of the pandemic, recalling an episode dated September in which Sidónio Pais takes a helping hand of 20 bags of sugar, 30 rice and 50 blankets.

In Lancashire, UK, the son of a family doctor, quoted by Mark Honigsbaum, recalls 1918: “There were so many patients that we only visited the worst cases. People collapsed in their homes, on the streets and at work. Many did not become conscious again. All treatments were in vain. ” In London, in October 1918, the deaths reached 4500 per week, numbers not much different from what we see today in Italy or Spain. Medical services across the UK quickly became inoperable, in a country that had one of the most advanced health systems in the world and which, after the epidemic, created the Ministry of Health (in Portugal it appeared 40 years later).

Isolation, an ancient technique

What Ricardo Jorge defended was summarized in a sentence, “bed, diet, herbal teas and doctor” – the same that the Royal College of Physicians recommended -, together with the isolation of the infected and other hygienic measures, such as not greeting people with their hands or give kisses.

The commissioner general of the epidemic never proposed, however, the general isolation of the population or the launch of sanitary cords such as that established for the bubonic plague in Porto in 1899 when I was a municipal doctor. “He thought he was going to sow the alarm and the effectiveness seemed debatable. Going too far in these measures would probably bring more negative aspects to the economy and social life, but in any case Ricardo Jorge also defended the restriction of the mobility of people and the public. For example, it banned large pilgrimages and fairs, at a time when an important part of economic life passed through here. He was also in favor of closing schools, but he did not want theaters, cinemas, cafés or public transport to be closed. ”

The 5th of October was not celebrated, but the National Theater organized at the end of that month a large exhibition of chrysanthemums, a social event always very popular.

In fact, the population flows were pointed out with the main responsible for the contagion between the different regions of the country: from the military migration associated with the displacement of troops in a country at war to the agricultural migration caused by the harvests in September, as well as the popular migrations linked to the fairs and pilgrimages in July, August and September.

“Social isolation is a classic ancient technique of dealing with pandemics. It is much before the 20th century and continued to impose itself on infectious and contagious diseases well into the 20th century through leprosaria, for example. Ricardo Jorge was not against isolation, but he thought the virus was so dangerous, so contagious, that the old confinement measures, such as isolating cities, would not work. There was such communication with millions of soldiers mobilized by the war that it was impossible to stop everything. In addition, isolation orders and instructions are one thing, and another thing is that they reach everywhere. ” In Coimbra, for example, a great procession of penance was organized asking for divine clemency against the scourge.

In The Forgotten Pandemic, a report by Arruda Furtado, inspector of Lisbon’s Civil Hospitals, then the most modern in the country, points to the “unbelievable and Moroccan” history of the Military Hospital of Campolide, in Lisbon, to which soldiers arrived from infected provinces such as Trás-os -Mounts, covering hundreds of kilometers, when hospitalization was intended not only to treat but to isolate those infected.

One of the main lessons that the 1918 pandemic teaches us, writes Mark Honigsbaum, “is that cities like St. Louis, in the United States, which acted early on and banned large public gatherings, closed schools and isolated patients or suspected cases , fared better than cities like Philadelphia that did not implement them ”Similar cases, points out José Manuel Sobral, were recorded in the Samoa archipelago, on the islands controlled by the Americans, and even in Australia.

Red Cross nurses in St. Louis, United States

Library of Congress

Perhaps Ricardo Jorge’s resistance to decreeing the isolation of cities during the Spanish flu can also be understood in the light of the traumatic outcome of the sanitary cord imposed in Porto in 1899. The doctor ended up as a refugee in Lisbon after receiving death threats, says José Manuel Sobral, but the challenge to Ricardo Jorge’s performance during the pneumonic was not particularly noted.

The same report by Arruda Furtado, dated 1920, also criticizes the excessive hospitalization of patients that led to the collapse of the hospital system, pointing out the importance of home care. But, the historian continues, it makes no sense to compare the 1918 health authorities’ response with the current one, because we are facing two radically different countries.

70% illiterate versus #fazatupartte

Although there was already a centralized tutelage in the health area in 1918, the group of institutions “was far from corresponding to the universalization of care that would become characteristic of the modern social and health services of the welfare state”, writes the historian. If institutions such as the Real Hospital de Crianças in 1882, the Hospital do Rego for infectious diseases in 1906, the first maternity hospital in 1911 or the Civil Hospitals of Lisbon in 1913 had already emerged in Porto, the Hospital de Santo António, the main hospital in Porto city hospital, where medicine was taught, belonged to Misericórdia. In José Manuel Sobral’s accounting, 63% of hospital care for patients on the Continent in 1915, according to data published in 1919, was done in private establishments. Of the 251 Portuguese hospitals, 96% were in the hands of private assistance, in the overwhelming majority of cases at Santa Casa da Misericórdia.

In a country with a medical and biological science in transition, which had experienced several successes but which was powerless in the face of this virus like the rest of the world, Ricardo Jorge with his exceptional powers is a symbol of the modern state that he takes as one of his main tasks to deal with the public health of its population in a code that prioritizes hospitalization and speed of hospitalization. “It is essential to have healthy populations in economic, symbolic and political terms. We are in a world in which the Portuguese soldier is poorer, more tuberculous and less tall than soldiers in Scandinavian countries or Germany ”, explains the Portuguese historian.

At a time when the very concept of population, brought up by demography and modern statistics, was still recent, letters appear in the newspapers that denounce those who “open doors to the disease”. A reader of The capital writes on October 8, 1918: “We have not been proceeding, as far as we know, the most elementary on the subject is put into action in countries where health, the lives of citizens, deserve care. The streets and squares of the capital are not fruitfully washed; disinfectants are not released into the gutters. In the center of Baixa, behind the Teatro de Dona Maria, there is a real source of infection. […] When the sun rises, clouds composed of flies, mosquitoes, melons and other insects […] constitute, as we know, a powerful element in the spread of epidemic ills. ” The letter, argues the Portuguese historian, is a mirror of an era that sees the idea of self-government in health emerging, albeit in an “incipient” way, a new social model, in which hygiene and health, well-being , should also be the responsibility of each one.