Phoenicians Engineered Water-Resistant Mortar Centuries Early

Discovery at Tell el-Burak Rewrites Ancient Construction History

Archaeologists in Lebanon have unearthed groundbreaking evidence of advanced construction techniques from the Iron Age. A recent study reveals the earliest known use of hydraulic lime plaster in the region, ingeniously developed by repurposing ceramic fragments.

Ingenious Recycled Materials

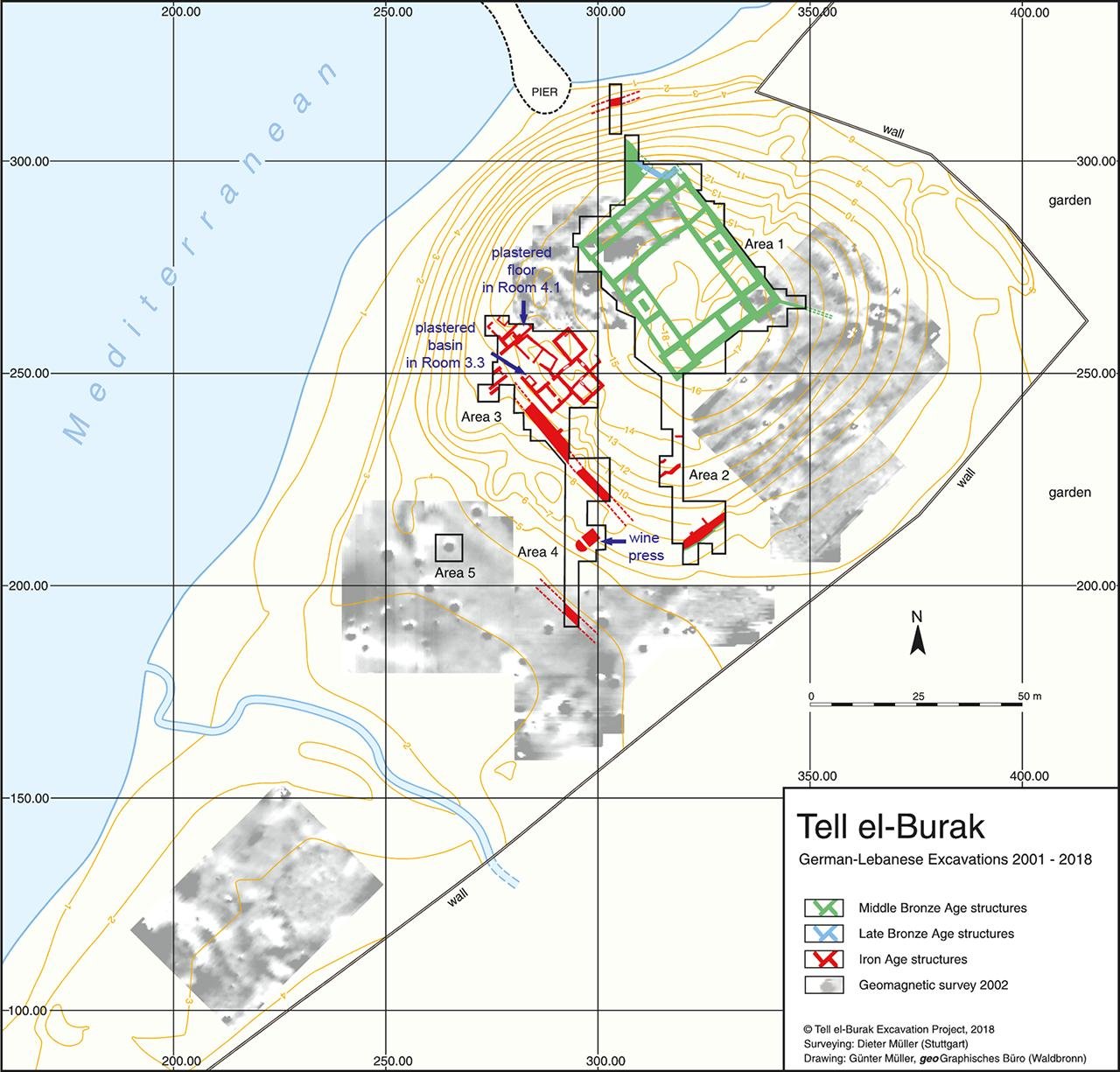

Excavations at the ancient Phoenician site of Tell el-Burak, active between 725 and 350 BCE, uncovered structures like a significant wine press and plastered basins. Analysis of the plaster used in these installations revealed a unique composition, distinct from standard ancient lime mixtures.

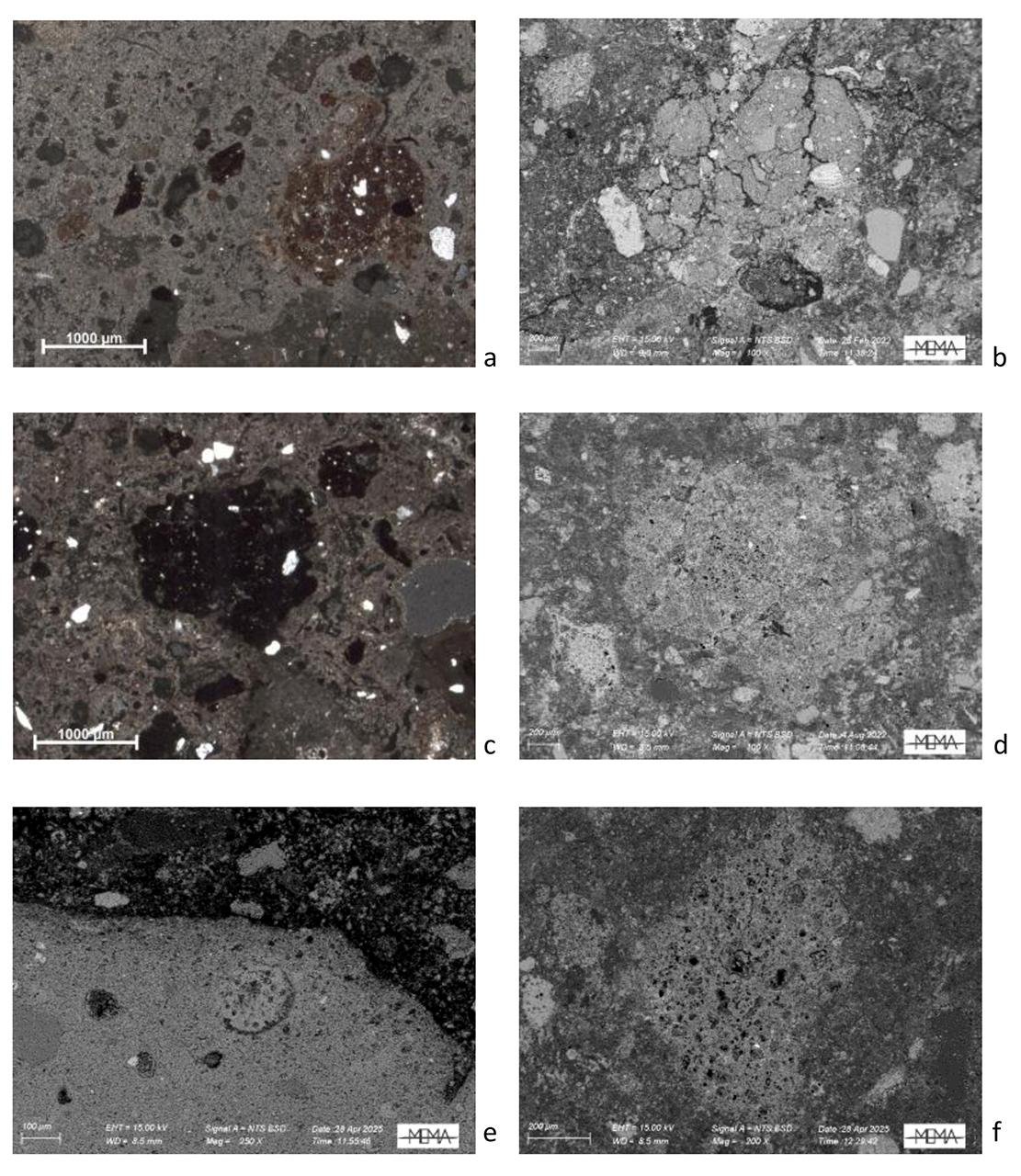

Scientists employed advanced techniques, including microscopy and X-ray diffraction, to identify the plaster’s components. They confirmed the presence of lime and local sand, but crucially, a substantial amount of crushed ceramic material.

Ceramic Innovation Creates Hydraulic Properties

The inclusion of ceramics was deliberate. Microscopic examination showed that the lime binder and ceramic fragments had chemically reacted, forming reaction rims. This interaction created a mortar that could harden effectively even in the presence of water, a key feature of hydraulic plaster.

This water-resistant quality would have been vital for structures like the wine press, which were constantly exposed to moisture. The reuse of broken pottery provided a durable solution, preventing erosion of more delicate materials.

Challenging Traditional Timelines

This finding suggests that sophisticated hydraulic mortar technology existed centuries earlier than previously attributed to Roman innovations using volcanic ash. The Phoenicians at Tell el-Burak achieved this water resistance through locally sourced, recycled ceramics.

The consistent use of this material across multiple installations at the site indicates it was a recognized craftsmanship tradition, not an isolated experiment. The builders demonstrated a deep understanding of modifying lime-based plasters for diverse functional needs within their agricultural complex.

The practice highlights the ingenuity of earlier cultures in repurposing materials for advanced engineering. This discovery potentially reshapes our understanding of technological development in ancient construction, suggesting a wider, earlier distribution of hydraulic mortar expertise.

Future research along the Phoenician coast may uncover similar uses of recycled ceramics, shedding further light on regional technological networks. For comparison, Roman concrete, a famed durable material, utilized pozzolanic ash and experienced a resurgence in popularity during the late Roman Republic and Empire, with some structures like the Pantheon still standing today due to its advanced properties (National Geographic).

This study underscores the innovative spirit of Iron Age builders, demonstrating that significant advancements in construction materials were being made long before commonly accepted timelines. The find at Tell el-Burak emphasizes the importance of looking beyond traditional narratives of technological progress.