Deported and Adrift: Cuban Migrants Face Uncertainty in Mexico Under Shifting US Policy

Recent shifts in US immigration policy have left many Cuban migrants deported to Mexico in a precarious situation, lacking clear pathways to regularization and facing an uncertain future. While Florida, home to the largest Cuban population in the US, has seen increased ICE detentions under programs like 287(g) – which delegates federal immigration authority to state and local police - the impact has disproportionately affected Guatemalan and Mexican communities. However,the past ten months have brought a marked change for Cubans,even those with naturalized relatives who supported the recent Republican administration.

According to immigration advocate Yaima Espinosa, US policy has transitioned “from protection to punishment.” Key programs offering humanitarian parole have been eliminated, work permits revoked, and deportations expanded, extending even to countries in Africa. This has placed hundreds of thousands of Cubans who entered the US legally at risk of detention and expulsion, while others live in constant fear of losing their established lives. Families are being separated, and a decades-long tradition of offering refuge to Cubans is being eroded, leaving many in a state of limbo.

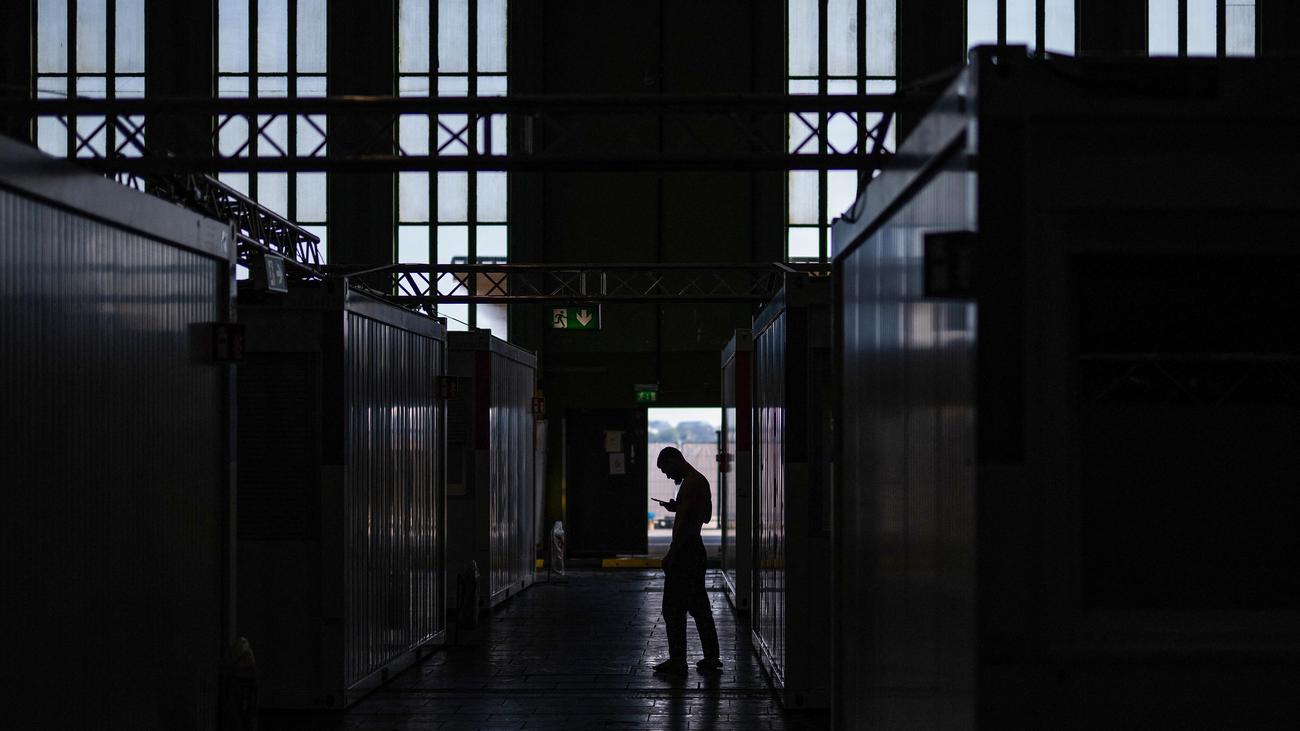

Laudel, a Cuban deportee, exemplifies this new reality.After being deported, he found himself stranded in Tapachula, Mexico, relying on the generosity of fellow Cubans for basic necessities like food and shelter.without documentation, securing employment proves nearly impractical. “I don’t have documents and that makes my situation worse. There is work, but without documentation it is impossible for a migrant,” he explained.

Mexican immigration law offers limited avenues for regularization for deportees. Immigration lawyer Irene Pascual advises presenting oneself to Mexican immigration authorities within 30 days of deportation and outlines three potential paths: regularization through family ties, humanitarian reasons, or proof of prior immigration history. However, Pascual notes that most deportees lack these qualifications.

Consequently, many Cubans are forced to seek refuge with the Mexican Commission for Aid to Refugees (COMAR), citing fears of persecution or imprisonment if they were to return to Cuba. While requesting refuge is a constitutional right, migrants report significant obstacles, including lengthy delays, denials of applications, and allegations of corruption, with some claiming to have been asked to pay over $1,000 for legal documentation.

Laudel has already submitted his case to COMAR and faces a wait of four to five months for a response. He firmly rejects the possibility of returning to Cuba, where his family has faced threats of re-imprisonment. A return to the United States is also not an option, leaving his future entirely dependent on the outcome of his asylum claim and his ability to navigate life in mexico.