A Disturbing Echo: A Review of Johann Chapoutot‘s Exploration of Nazi Ideology in Management

Johann Chapoutot’s work presents a provocative and unsettling thesis: that the managerial philosophies prevalent today bear a disturbing resemblance to, and may even have roots in, the ideologies espoused by the Nazi regime. The book skillfully interweaves a core narrative wiht a compelling secondary storyline featuring two female executives grappling with the pressures and contradictions of modern management, one having experienced burnout as a result.this framing device effectively highlights the human cost of the very systems Chapoutot dissects.

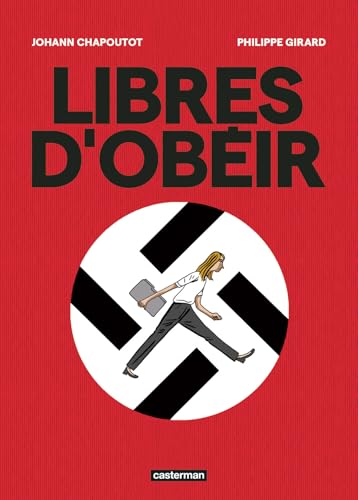

The author meticulously documents parallels between contemporary management speak and the tenets of Nazi thought. He points to a “trompe-l’oeil” system where employee growth is ostensibly prioritized, yet harshly penalized for failing to meet predetermined objectives, creating a facade of freedom masking a predetermined outcome. This echoes a pseudo-democratic structure where employees are encouraged to “consent to their fate” within a carefully controlled environment. Philippe Girard’s clear and concise illustration style complements the book’s serious subject matter, successfully navigating the challenge of maintaining reader engagement while presenting a wealth of documented references.

Central to Chapoutot’s argument is the story of Reinhard Höhn, a former SS officer who not only survived the war but leveraged his networks to establish a management school in the United States. Between 1956 and 2000, this school trained an astounding 600,000 executives, many under the guidance of former SD and SS members.The author convincingly demonstrates Höhn’s influence on post-war German management practices, even acknowledging the later criticisms leveled against him and his past. Chapoutot’s research and expertise are beyond reproach.

Though, despite the book’s captivating nature and rigorous scholarship, it leaves a lingering sense of incompleteness. While the connection to German management is well-established, the argument for a broader, global influence feels less substantiated. The claim that current, internationalized managerial philosophy stems from these Nazi theories, even partially, feels like a leap. The book cites the origin of the term “human resources” as a potential link, but lacks further concrete evidence to support a widespread impact beyond Germany.

The dominance of Anglo-Saxon, especially American, financial capitalism throughout the 20th century, and the distinct “newspeak” that accompanied it, seems a crucial element missing from the analysis. The author’s focus remains largely confined to the German context, potentially overlooking the realities of management practices elsewhere. One is left to wonder if the “deleterious practices” identified aren’t simply inherent to capitalism itself – a system that, historically, has adapted and absorbed whatever serves its relentless pursuit of growth, frequently enough without the need for specific ideological blueprints. Perhaps these practices reflect a “natural order” driven by economic imperatives, a concept ironically echoed by the Nazis themselves.

Despite this critical reservation, Chapoutot’s work remains a valuable and thought-provoking contribution. It is indeed a consistently insightful, if somewhat narrowly focused, exploration of a disturbing possibility. The book concludes with a powerful call to individual agency, reminding us that “the real way of being free is to disobey!” – a sentiment that resonates long after the final page is turned.