New Approach to Space Exploration May Protect Other Worlds

As humanity delves further into space, safeguarding alien environments from terrestrial microbes is crucial. A recent study suggests that we may need to rethink planetary protection by using island biogeography principles, offering potentially more effective strategies.

Rethinking Planetary Protection Strategies

Current planetary protection protocols depend on probabilistic modeling. These models evaluate the likelihood of microorganisms enduring the journey to Mars, successfully landing, and establishing populations. For instance, NASA’s guidelines stipulate a maximum 0.1% probability of Mars contamination during any single mission. However, this method presents significant shortcomings.

The problem, according to researchers from the University of Edinburgh, is that these probabilistic models primarily treat contamination as a matter of numbers. They concentrate on minimizing the initial microbial load on spacecraft and calculating survival chances. They often overlook what occurs after microbes reach their destination.

Island Biogeography: A New Perspective

Researchers propose considering planets as analogous to islands in Earth’s oceans. Similar to how island biogeography explains species colonization and survival on isolated landmasses, these same ideas might control microbial survival on distant worlds. Both planets and islands are physically separated locations where small organisms might arrive and strive to establish populations.

This perspective moves away from probabilities, concentrating on a more fundamental question: can arriving microorganisms actually survive and multiply in the target environment? Instead of asking, what are the odds of contamination?

the new approach queries, will these microbes have a mean-time to extinction long enough to establish a lasting population?

Survival Conditions

A fundamental idea is that microbial growth is binary. A microbe either finds conditions ideal for survival and reproduction or it does not. If the birth rate surpasses the death rate, populations will grow. Otherwise, they will eventually vanish.

The researchers suggest that successful colonization hinges on whether organisms can achieve a sufficiently long mean-time to extinction. This is influenced by environmental factors, including temperature, pressure, acidity, and available nutrients. By mapping the ranges of conditions where organisms can persist, scientists could more accurately predict contamination risk.

Practical Application

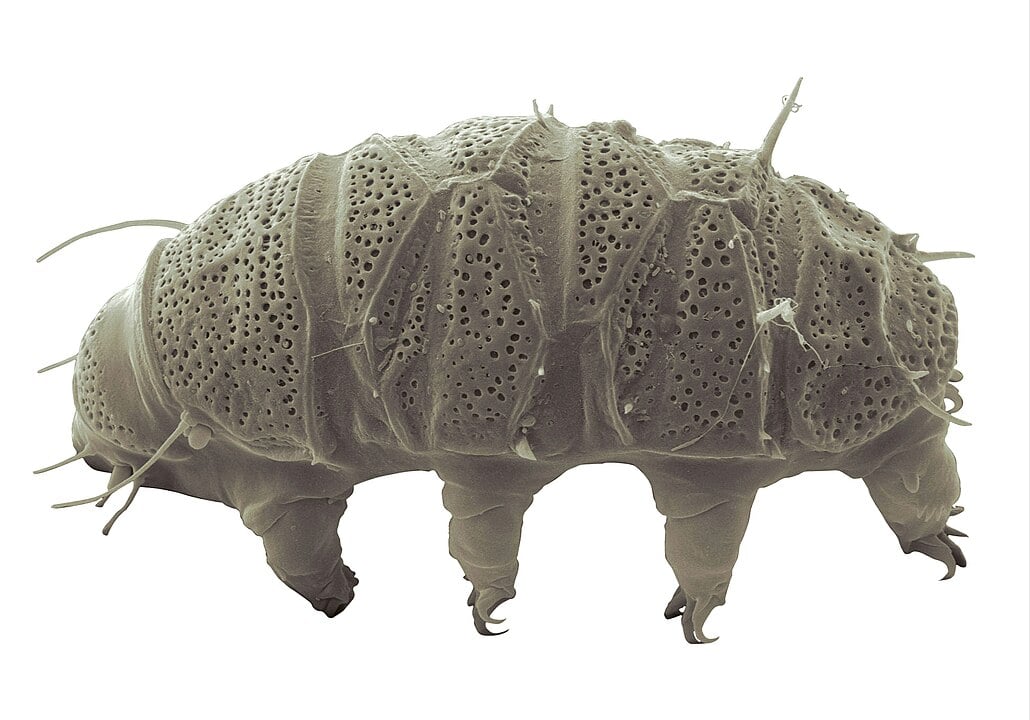

This framework may prove especially valuable for missions to Mars, where several environmental stressors, such as severe cold, low pressure, radiation, and toxic soil chemicals, create challenging conditions that most terrestrial life cannot survive. The research suggests creating a catalog of Earth organisms that can survive different planetary conditions. This would help mission planners identify which microbes pose genuine contamination risks for specific destinations.

This island biogeography approach marks a shift from probabilistic guesswork to environmental analysis grounded in fundamental biological principles. For example, a 2024 study indicated that over 99% of the Earth’s known microbial species are still uncultured, underscoring the complexity in protecting extraterrestrial environments from these unknown life forms (Nature, 2024).

By understanding whether alien worlds can support Earth life, we can create more focused, effective strategies for planetary protection.