Mitochondria Transplants Offer New Hope for Damaged Organs

Tiny cellular powerhouses show promise in healing injured tissues

A groundbreaking approach utilizing mitochondria transplantation is emerging as a powerful new tool in regenerative medicine, offering hope for repairing tissues damaged by various conditions. This innovative therapy involves injecting healthy mitochondria into injured areas, aiming to restore cellular function and promote healing.

Accidental Discovery Sparks a New Field

The potential of mitochondria transplantation was first observed nearly two decades ago when surgeon James McCully at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School was experimenting with extracting mitochondria. During a procedure on a pig heart that refused to pump normally, McCully injected extracted mitochondria into the organ. To his astonishment, the heart began to beat, regaining its healthy color.

This unexpected success led to years of animal studies and eventually human trials. Researchers found that these tiny, energy-producing organelles not only fuel cells but also play crucial roles in cellular signaling, immunity, and stress responses. The technique is now being explored for a range of conditions, including heart damage after cardiac arrest, brain injuries from strokes, and damage to organs awaiting transplantation.

Pioneering Use in Infant Heart Surgery

Around ten years ago, cardiac surgeon Sitaram Emani from Boston Children’s Hospital collaborated with McCully to apply this method to infants suffering from complications after heart surgery. Babies undergoing surgical repairs for heart defects often require their hearts to be stopped temporarily. Prolonged deprivation of blood and oxygen can lead to mitochondrial failure and cell death, a condition known as ischemia.

In a pilot study conducted from 2015 to 2018, McCully and his team extracted mitochondria from muscle samples, ensuring their functionality, and injected them into the hearts of 10 infants. The results were significant: eight of these infants recovered sufficiently to be removed from life support. This contrasts with historical data where only four out of 14 similar cases achieved this outcome. The recovery time was also notably shorter, averaging two days compared to nine days in the control group.

Extending Hope to Stroke and Organ Donation

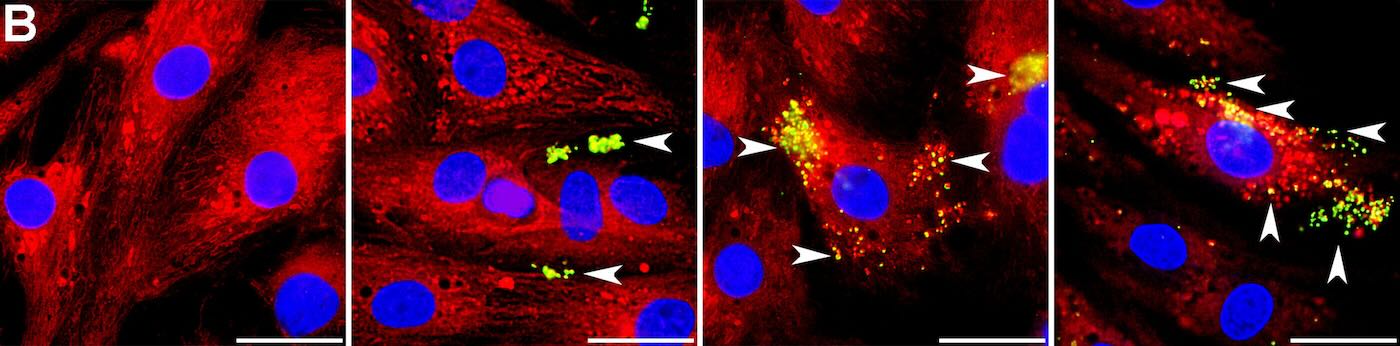

The promising results have encouraged other researchers, such as Walker, who studies ischemic stroke. She learned that astrocytes, the brain’s support cells, may naturally transfer mitochondria to neurons damaged by strokes. Her team conducted a small clinical trial, delivering mitochondria to the brains of four individuals with ischemic stroke using a catheter-based method. The trial, published in 2024, reported no harm to participants, with further studies planned to assess efficacy.

The application extends to organ donation as well. Transplant surgeon-scientist Giuseppe Orlando at Wake Forest University School of Medicine explored mitochondria transplantation in pig kidneys. His team found that treated kidneys exhibited fewer dying cells and reduced damage, along with increased energy production, compared to control kidneys. This suggests that mitochondria therapy could potentially rescue marginal organs for transplantation.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the excitement, challenges remain. Koning Shen, a mitochondrial biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, highlights the technical hurdles in scaling up mitochondria extraction and developing reliable storage methods. Navdeep Chandel, a mitochondria researcher at Northwestern University, points out the need to fully understand the underlying mechanisms, suggesting that donor mitochondria might indirectly benefit damaged tissue by triggering stress and immune signals.

Studies by Lance Becker, chair of emergency medicine at Northwell Health, indicate that functional mitochondria are key. His research on rats following cardiac arrest showed that fresh, viable mitochondria improved brain function and survival rates, while frozen-thawed, non-functional mitochondria did not. The ultimate goal is to establish a “mitochondria bank” for widespread clinical use, awaiting FDA approval through further research, larger trials, and a clear understanding of the therapeutic mechanisms.